This is an excerpt from my ebook, How to Design Card Games.

The purpose of playtesting is to collect real-world experiences with your game that you can use to help you modify your game so that it better achieves your goals. Early on, you might playtest the game by yourself (solo playtesting or self-testing) to make certain that its basic framework works or to test individual parts of the game. Your friends and family members will want to play a more workable version of the game, though it is best to emphasize the goal is to learn about the game rather than win. Your target audience is approached through blind playtests, where they learn the game as your players will eventually in the real world – from the documentation and game components alone.

For a brand new idea, you want to test that the game actually works and is fun, and keep track of where ideas don’t proceed as you expect. Try to schedule time to play it through 2 or 3 times, so you can see the game under different conditions.

Come up with a list of the goals you want to accomplish during a playtesting session. Perhaps you want to test certain conditions that arise when the game is over. Or you need to test just the combat system. In such cases, you do not have to play the entire game. For instance, for one game my son developed, one of our play-test sessions involved just testing different ideas for combat, which was just one part of the game. You might want to test different scenarios: the end game, rare events, edge cases, points that have confused earlier testers, etc.

[source: https://www.slideshare.net/dmullich/lafs-game-design-8-playtesting]

Goals for playtesting, and who you should playtest with, often depend on where you are in the development of this particular game:

- Initial idea / zero draft – Quickly get a subset of the game to the table to verify that the mechanics work the way you intend, with a proto-prototype, as it were. Just play by yourself or with a fellow designer.

- First draft – Playtest with other designers or with good friends who won’t mind playing a broken game to see if the game works.

- Subsequent drafts: Playtest it repeatedly with different groups to determine what needs to be refined. This is where you will spend most of your time.

- Balancing: Send it out for blind playtests and log feedback, to make sure cards aren’t unbalanced. Play it with groups with the goal to try and break it.

Brandon Rollins defines blind playtesting as “When you give your game to other people with no instructions on how to play. You can choose to observe them while playing or elicit their feedback after the game has ended.”

If you are only planning on playing your games with friends, you may not need to do blind playtesting. Once the game is almost done, though, you can recruit playtesters over the Internet or give the game to acquaintances to play without you.

Steve Jackson says “good advice for any designer” is “playtest the dumb strategies.” For instance, in a game with a range of actions, what happens if a player takes the same action or two every turn? In the Kobold Guide to Board Game Design, the following strategy broke an earlier version of Dominion: “In the initial stage of the game, Dominion ended when any one of the three Victory stacks were depleted. So, the Duchy Rush strategy had a simple algorithm: buying nothing if you had 0 to 2 coins in your hand, buying a Silver if you had 3 or 4 coins in your hand, and buying a Duchy if you had 5 or more coins in your hand. That’s it. This strategy totally ignored all of the Kingdom cards on the table.” The game was changed prior to publication to add end conditions and to tweak victory points to make this a suboptimal strategy.

Surviving Negative Feedback

Keep in mind when playing with people in person that it is human nature to tell people what you think they want to hear – your playtesters might give you pleasant platitudes. Make sure you emphasize the value of negative feedback and constructive criticism. If you can ask only one question, ask:

- What one thing would you change to make the game more enjoyable?

Other good questions:

- What confused you the most about the game?

- What, if anything, would you change about the game?

- What, if anything, would you make sure not to change?

As we’ve all learnt by now, people are much more caustic over the Internet. At one point, Android: Netrunner was the most highly rated card game on BoardGameGeek.com, with an average rating of 8.1 on a 1 to 10 scale. Here are a sampling of the comments of those who rated a 1 what is widely regarded as the best card game:

- “One more example of a game loaded up so heavily on theme that the gameplay totally suffered. I really, really don’t know why this game has gathered as much popularity as it has.”

- “This is one of the most absurdly luck based games I have ever played. Why design a game where if you don’t draw the exact types of cards you need, you lose?”

- “Stupid ‘game’. Stupid manual. Stay away from it.”

- “It feels like there’s way more stuff in the game than there needs to be. It might be fun if it were streamlined. But it’s not, and it’s not. The runner died on his first turn during one of the games I played.”

- “The mechanics kill it for me… The overall dynamic means the game plays you… I don’t think you should buy this game.“

- “Run in the other direction! Now!”

Even one of the best card games doesn’t appeal to everyone. Now, imagine the designers, Richard Garfield and Lukas Litzsinger, were playtesting the game and got those comments. They’d feel like the game was a failure, right?

Sometimes a game is not right for a playtester, or group of playtesters. That doesn’t mean it is a bad game. My game Civscape, provided below, is a simple take-that card game about the rise and fall of city-states. When I playtested it with a group of game designers, they all hated it. They wanted something meaty and mathy and strategic, like most civilization games, while Civscape is meant as a fun filler before or after the main game of the evening. I was so discouraged I set the game aside for a year. Until I heard from another playtesting group that had friends who wanted to buy their own copies. Same game: completely opposite reaction.

Apply the feedback that matches your design goals. For instance, one of my friends who is a game designer has a simple family game, and she had two different actions: one where people draw 3 cards from Deck A and add 1 card to their hand, and one where people draw 2 cards from Deck B and add to their hand, then discard 1 card from their hand. My advice to her was to make this action consistent, regardless of deck; since that met her design goals, she did, standardizing on “add to hand, then discard”.

So learn from feedback, but don’t take it to heart. Not every player loves every game.

One last bit of advice, from Steve Jackson: “If your testers say it takes too long, what they really mean is they’re not having enough fun.”

How Much Playtesting Is Needed?

How many playtests are enough? Partly it depends on how quickly the game comes together. Partly it depends on game complexity: the more complicated the game, the longer it will take to playtest. Partly it depends on the intended audience: for friends and family, a few playtests are sufficient; for people to download free on the internet, at least 10; for publication, probably at least 50. And Tom Jolly would argue you need to play a game 100 times.

I was lucky in that my game City Blocks, published by Nestorgames and available to play for free on Yucata.de, came together in one afternoon of playtesting. But it was an extremely simple game. My game Civscape Rivals (included as the final example game in this book) took over 250 plays over 4 years before I felt it was ready for publication.

Very long games can be challenging to playtest. I once rented a table at a boardgame convention and playtested the same game dozens of times over 3 days with a hundred attendees. A well-regarded game designer from a major publisher, who has multiple games in the BoardGameGeek Top 100, confessed that we were playtesting the game far more than they tested their titles.

Playtest, playtest, playtest!

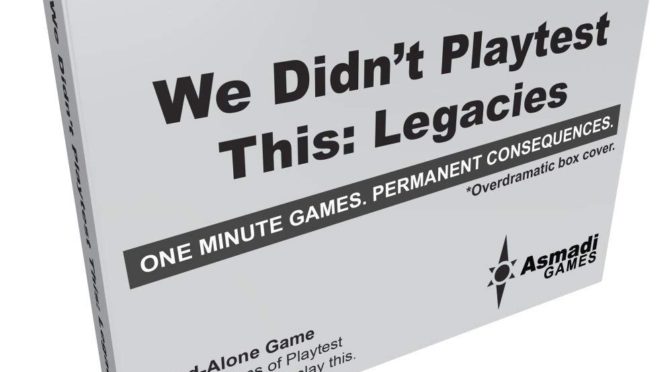

As the Asmadi game featured in our cover image warns, not playtesting leaves its legacy.