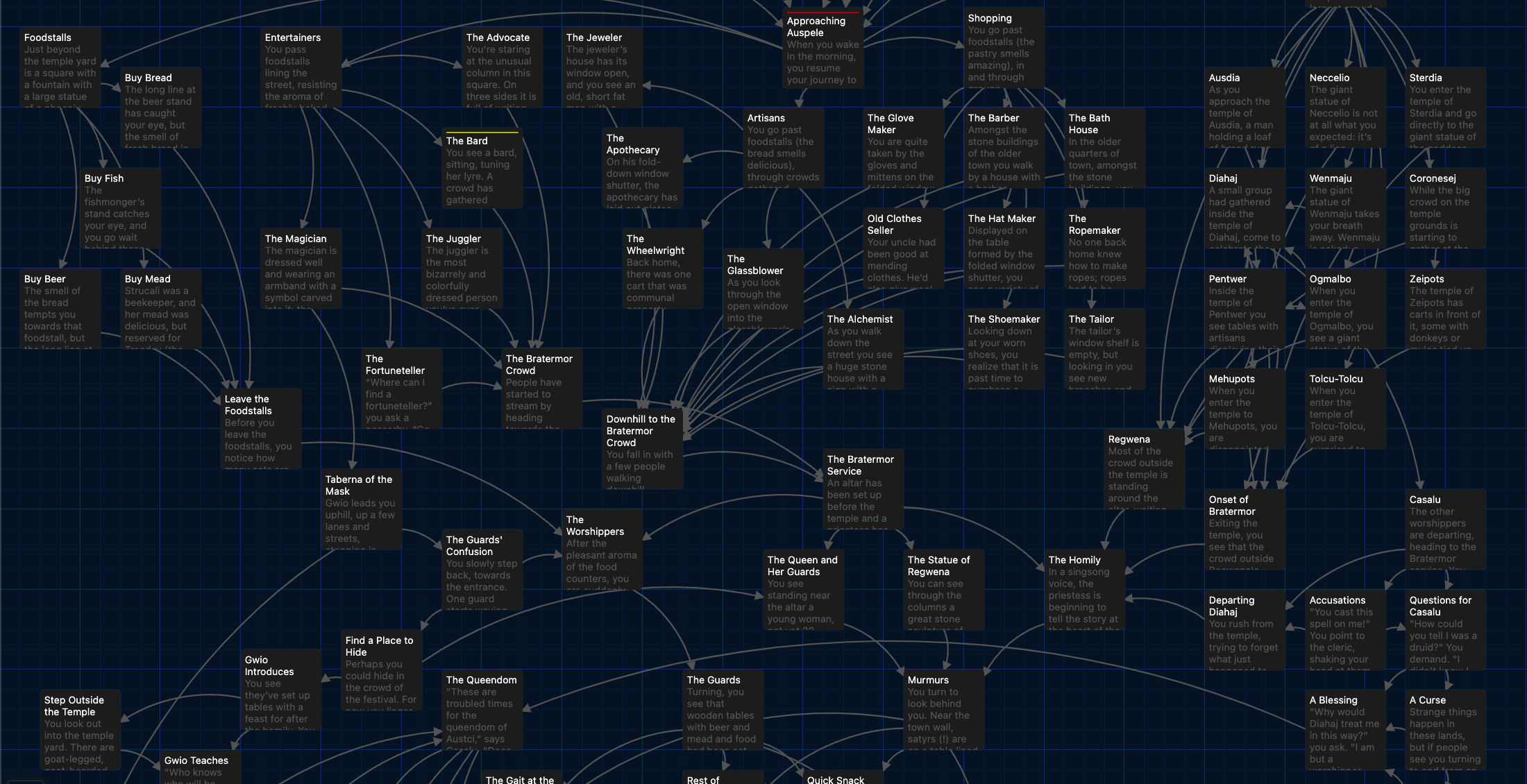

In Emily Short’s classic blog post “Small Scale Structures in CYOA,” she wrote about local structures (as opposed to narrative structures that describe the entire work). She was interested in structures that could use stats, as in Choice of Games or Twine games. I instead want to concentrate on the traditional finite-state machines that are CYOA stories. The only variable is the page you are on or the number of the block you are in. I’ll use lightly-edited screenshots from Twine from my game, A New Life in Auspele, to illustrate each.

Branches that Later Merge

Diversions

Diversions are impactless choices, affecting only the narrative flow and what happens in the fiction.

Here’s a stage in a journey, where the precise route you take doesn’t affect subsequent choices. That said, you experience different narrative color depending on the path you chose.

Lore Dumps

Some of the IF games I’ve played, at Choice of Games and on Twine, let you have conversations with NPCs where you ask every question listed, or all but one question. When I provide such lore dumps, I prefer to have the reader pick only one choice, then advance the story. A lore dump is a diversion with the goal of educating.

Here is a more traditionally structured lore dump, where each passage points to the others.

The Shortcut

The shortcut is useful for replay, where you can bypass items that are important to know on the first playthrough but don’t need to be revisited in subsequent plays. It’s like a lore dump but with an escape route or exit.

Here are the first choices in my game: “Strucali hands you the staters and a few smaller coins. Do you look closely at the coins? Or do you worry out loud about thieves? Or do you ask her for advice on the best way to Auspele? Or do you get ready to go?” The first few playthroughs you probably want to ask her some questions. Eventually you know the other answers and just want to set off.

Linear Progression

One block after another, as I use them, implies a change in focus, such as elapsed time or a shift to a new location or scene. Many Twine authors seem to use these to slowly unfold information, a bit at a time.

Obviously, from a strict nodal design, they could all be combined into one node in the tree.

Bottleneck

In my first draft of Auspele, there was a bottleneck early in the story. The reader could choose three different travel directions, than three or so different paths for each of those, all coming back together at the city gate. This allowed me to add variety to the start of the story and to show different aspects of the world and the reaction of the main character to them.

There was then another bottleneck after a large number of possible paths the reader could take to first explore the city before the start of a major festival. Both of these bottlenecks helped manage the complexity.

Branches Without Merging

Irrevocable Branch

An irrevocable branch is a choice that permanently changes the state: no reuniting later in the story.

At the midgame, I have a few instances of what I call Monty Hall Prep when GMing, where key meaningful decisions dictate the focus of the rest of the action.

But irrevocable branches are more common at the end of the story. I’m not going to call this a dilemma because that implies that both options are equally unfavorable.

The Fan

The fan offers many choices, some that impact the subsequent direction, some that don’t. I use the fan for world building and flavor, and to provide variety at the start of the story (as Emily Short does with The Sorting Hat, though she is tracking states).

Early on in my Twine game you have a choice of visiting one of the twelve temples (one for each of the gods of my one-page pantheon). Most of these temples just showcase one aspect of faith in Auspele, but a few change the course of the rest of the game. And, since the temples are adjacent to one another, sometimes a temple’s text offers you the chance to visit another temple.

And here’s another example, where you’ve decided to go find food, and—in one of the paths—find much more.

Sudden Death

These are the sudden, often unexpected end to the story. These were a common means of pruning the tree of choices and simplifying the overall structure back in the heyday of Choose Your Own Adventure books. In the computer and adventure games of the 1970s and 1980s, sudden death was a much more frequent end to a game than it is today.

I prefer to telegraph the risk as much as possible, so you’re not surprised when you suddenly die or end the story.

Narrative Experience as a State

Many of these structures—Diversions, Lore Dumps, Shortcuts, Linear Progression—all reconnect at a single common node or Bottleneck, meaning the availability of subsequent paths hasn’t changed. And even Fans often reconnect at just a few nodes.

But what has changed is the reader. They’ve experienced a different story than they would have otherwise, even though their simple state—in terms of the numbered page or block they are on—is the same. But on a first read-through they have access to information they wouldn’t have seen if they’d chosen another path. This might be a tip, a warning, or foreshadowing.

In one of the paths traveling to the city of Auspele, for instance, you encounter someone who advises you to go to a specific place in the city. That gives you a reason to consider making a subsequent choice.

After all, the impact of choices in interactive fiction is all in the mind of the reader anyway.