Growing up, I remember going to friends’ houses and typing in BASIC programs. We’d take turns entering the listing and double checking it, then play whatever game it was. Back then, everyone had a different microcomputer. I had a TRS-80 Model I, the library had an Apple II (too expensive for most of us back then), Ron had a VIC-20, Mark had a TI-99/4A, Mike had a Commodore 64, Chris an Amiga, and so on. Even the Bally Astrocade had a BASIC cartridge.

The iOS app LowRes Coder returns us to those glory days of BASIC programs, though without line numbers and with some structured programming: WHILE loops, REPEAT-UNTIL loops, DO loops, and multiline IF / ELSE IF / ELSE / END IF structures (heck, TRS-80 Level I BASIC didn’t even have an ELSE statement, let alone anything but a FOR loop!). No argument passing into subroutines though: still GOSUB and global variables.

The free version of the LowRes Coder app only lets people write 24-line programs. An arbitrary limit, yet a limit that inspired one user, Was8bit, to post this challenge:

I’ve posted several microgames … I challenge others to post their own microgames; it’s a fun challenge. Must follow these guidelines:

1) 24 lines of code, no more than…

2) Highlight one or a few programming skills or techniques

3) Should help give a new programmer a place to start learning by tinkering with your code, and/or have a concept that inspires similar games….

I’ve burned myself out with it, so I pass the torch to others… would like to see you try at least one microgame to help contribute 😀

The nice thing about a 24-line program is that it can be written and debugged in an evening, so it has a realizable end state. And it actually has some value as a prototyping tool (more on that in a bit). Or as the working version for a planned, fuller game, to be developed agilely.

My initial thinking was that only the classic Teletype interface programs where you enter numbers would be suitable for microgames: Guess, Lemonade Stand, Hamurabi, Lunar Lander, etc. To that end, I wrote Lemonade Stand 24.

But once that was done I decided to take another stab at a Connect Four clone. I had written it on the Apple II at our public library, inspired by my dad’s Tic-Tac-Toe program for our TRS-80. (Dad had built a Tic-Tac-Toe machine on a GENIAC as a kid.) I definitely had to compromise to get something to work in 24 lines: you can’t win by playing diagonally and the AI is pretty poor. (Check out The Complete Book of CONNECT 4: History, Strategy, Puzzles.) Clearly this is a programming exercise that would be mainly about the AI rather than the UI. Here it is: 4 In A Row.

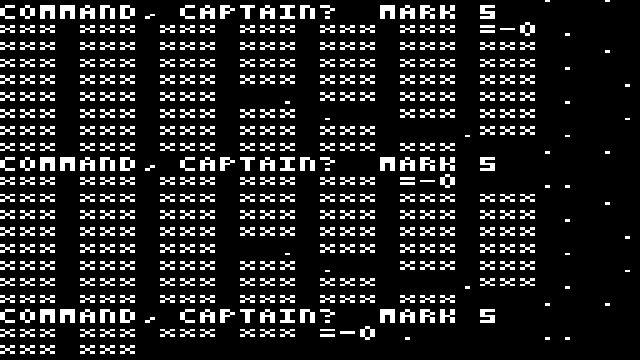

I’ve been wanting to replay the Trek 80 program from my TRS-80 – it was my favorite game back then, but I haven’t been able to track it down. Turns out there were a lot of different Trek implementations. This video gives you a taste of the experience in the 1970s, though my version didn’t have those snazzy graphics: my version had =-0 for the Enterprise and >-0 for the Klingons. It did show a photon torpedo (an ASCII period) close in on its target though. So here’s Trek 24, where you must destroy all the Klingons before they destroy the Enterprise.

I wanted to take a stab at a Pong-era arcade game. (I can remember playing video games that were in black and white at the first arcade I ever went to.) I wasn’t sure what I could fit in 24 lines, but started over-ambitiously with a platformer – it instead evolved into a game of avoiding a sentry robot as it moves more and more quickly through level after level. The game supports 16 levels of accelerating velocity, almost each a different color, before restarting at the slower pace: SentryBot 24.

I’ve been interested in writing my own roguelike for a while now, but that always seemed too ambitious. Limiting it to 24 lines however – now there was a project I’d be able to actually finish. So, yes, I implemented a roguelike with 20 monsters and 18 items: in 24 lines of code! Roguelike 24.

When Was8bit started this challenge, I didn’t think you could do much with 24 lines. Perhaps some guessing games or simple simulations. But, in fact, you can accomplish a lot in 24 lines. Beyond the competition, the approach is useful to rapidly prototype an idea. I can see using it again for prototyping games, game subsystems, and levels, too. If you’re writing a new dungeon crawler, whether a card game, board game, or video game, why not prototype it as an ASCII roguelike first? A microgame is a great way to see if the foundation of a game design provides a sense of engaging play.

Tips for Writing Microgames

Interested in writing your own 24-line programs? Some tips I’ve discovered.

Push complexity from the game to the documentation. The list of monsters and objects in Roguelike 24 is close to 40 lines alone! With any game, much of the complexity and verisimilitude is in the player’s mind anyway, not the game itself. Hence the continued niche appeal of pixel games, interactive fiction, and ASCII roguelikes. And Dungeon & Dragons and Pathfinder games mainly take place in players’ imaginations.

Oversimplify the game design to concentrate on essentials. In my 4 In A Row, you can’t win diagonally – too hard to implement given the limit on the number of lines of code. In Roguelike 24, the strength of a monster is its ASCII code minus 64: Ant, 1; Bat, 2; Dwarf, 4; Zombie King, 26. I curated the list of monsters around this property (no D for Dragon and G for Giant in this scheme, for instance) and made it a Zombie King and not a Zombie. In Trek 24, instead of having Klingons detected when going to a new region, I have them show up in the region you just left—much simpler to code! Instead of detecting collisions, presumably the Klingons warp out of the way when you try to ram them. And so on.

Create the world as the player moves. When lines of code aren’t the constraint, it’s typically better to initialize the world and then store the state of the world (e.g., whether a room has been explored; see my Colossal Cave Adventure 101 for an example). In a microgame, create each quadrant of the galaxy or cell of the dungeon as it is explored.

Oversimplify data structures. Typically, clear data structures produce code that is easier to read and maintain. But that’s a luxury when you have 24 lines. Instead of having a two-dimensional array to represent a grid in Trek 24, I used a one-dimensional array. Couldn’t afford two FOR loops to display a matrix, plus two lines per move (e.g., X = X+1 and Y = Y+1 for Mark 8). I also made the arrays larger than necessary to eliminate the need for bounds checking. For Roguelike 24, I gave up on the array altogether and just manipulated a single string that represented the dungeon grid and used a fixed-width font to print it across multiple lines without line breaks.

Use strings for lists and sets. But don’t tell Mr. Ryden, my high-school computer-science teacher. Since 8-bit BASICs lack user defined types, use strings liberally. If you are using another language, user defined types probably would take too many lines of code, anyway. In Roguelike 24, new items are appended to INV$ to track inventory, and INSTR is used to determine if an item is in the inventory when trying to use it. Easy since items have a one-character code but I’ve used CSV (Comma-Separated Values) in other programs: e.g., “,ANT,BAT,GIANT,”, with the series string beginning and ending with a comma and with INSTR(MONSTERS$, “,”+M$+”,”) so that substrings aren’t false positives (e.g., so “ANT” isn’t found in “GIANT”).

Forget AIs to instead rely on random behavior—or no behavior. A game like Atari 2600’s Adventure implemented simple behaviorism through Finite State Machines for the dragons and the bat. But even such a simple model is too much code for this challenge. In Trek 24, Klingons never move. In 4 In A Row, the computer plays in the column you just played to or one of its neighboring columns at random. (Which is technically a tiny AI: the first version just selected a column at random, which was even easier to beat; now the game usually at least makes you work a little bit for the win.)

Specific Programming Tips

Writing to an arbitrary line limit does obfuscate the code in places, as a side effect. Here’s some tips for staying within 24 lines, readability aside.

Collapse multiline IF statements or refactor. For instance:

IF X=0 THEN Y=1 Z=2 ENDIF

…becomes…

IF X=0 THEN Y=1 IF X=0 THEN Z=2

Or perhaps you can use SGN(). For instance, 10*SGN(PLAYER-ENEMY) gives a 10-point penalty if the player is weaker, a 10-point bonus if stronger, and has no effect if the player and enemy are equal. Better for minimizing cyclomatic complexity.

GOTO considered helpful. Helpful for saving lines, that is. In “Micro Game – Frog”, Was8bit adopts an old assembly-language technique of overincrementing so that one routine can fall through to the next (math is faster than jumps and saves code):

DORIGHT: PX=PX+16 DOLEFT: PX=PX-8 LAYER 1 CLS CIRCLE PX+4,60,4 PAINT

Offset values from 0 instead of initializing. For instance, instead of:

SHIELDS = 100 SHIELDS = SHIELDS-10 PRINT "SHIELDS AT " + SHIELDS IF SHIELDS <= 0 THEN PRINT “YOU LOSE”

…use…

SHIELDS = SHIELDS-10 PRINT "SHIELDS AT " + (SHIELDS+100) IF SHIELDS <= -100 THEN PRINT “YOU LOSE”

Move initialization FOR loops into the game. Part of the general philosophy of building the world as play goes on rather than procedurally generating it up front includes initialization, not just discovery.

FOR X= 1 TO 10 A(X) = RND*10 NEXT X … FOR X =1 TO 10 PRINT A(X); NEXT X

…saves two lines when done this way…

FOR X=1 TO 10 IF A(X)=0 THEN A(X) = RND*10 PRINT X(A); NEXT X

Tolerate errors. You can’t error check all user input and all game conditions. In 4 In A Row, playing your checker to a full column just causes you to lose your turn rather than prompting you for a different column selection. (This might be a nice equalizer against the AI, in this case, but the AI actually does this far more often than a human player would.)

To force user input into a range, use this formula:

MAX(1, MIN(M, 8))

If the player enters a number lower than the minimum, it is treated like the minimum (in this case, 1). If more than the maximum, it is treated like the maximum (in this case, 8).

Use strings as lookup functions instead of having arrays or READ/DATA statements. Here is an example for Trek 24 for navigation from Mark 1 to Mark 8:

MID$(" 1-7-8-9-1 7 8 9", CMD*2-1, 2)

This is analogous to the Excel function CHOOSE; e.g., CHOOSE(CMD, 1, -7, -8, -9, -1, 7, 8, 9). Here’s the lookup for movement distance in Roguelike 24:

MID$( "+0-8+8+1-112",INSTR("NSEWT",CMD$)*2+1,2)

North is -8, South is +8, East is +1, West is -1, and Teleport is +12. If no command is found, +0 is returned.

In Roguelike 24, INSTR is used to find the relative strength of each weapon and also to find the bane (from a 26-character string) that corresponds to the monster being fought.

Call to Code

So you’ve been wanting to design a game but are overwhelmed by the size of the project? Try a microgame instead! If you have an iOS device, download LowRes Coder or try the language of your choice in a browser (Try It Online).

Happy coding!

You must be logged in to post a comment.